The economists have a consensus?there will be no rate cut on August 5, 2014. The question remains?how much of this forecast is based on herd mentality, and how much is based on data that RBI must consider before making interest rate policy?

The most important variable determining the present RBI stance on interest rates is inflation as measured by the CPI. In the last policy statement (June 2014), RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan stated: ? ?if disinflation, adjusting for base effect, is faster than currently anticipated, it will provide headroom for an easing of the policy stance?. Translated into English, what Rajan said was that if there is a decline in the rate of inflation, and this decline is not due to seasonal factors; and not due to abnormally low inflation in the comparison month last year (base effect), then RBI will have a valid basis (headroom) for an easing of monetary policy.

Regarding the base effect. Last year, the yoy CPI inflation March through June was 9.1%, a value lower than the first six months average of 9.6% (yoy figures not reported in the accompanying table). Thus, the base effect goes the other way, i.e. if inflation in 2014 is lower, it is because of structural factors, and not due to seasonal biases.

The seasonal effect of inflation is best examined by the use of seasonal factors, a science considerably well-developed in the West. Most policy-makers in the world use seasonal factors in order to determine the course of structural variables like output and prices. For some unknown reason, RBI has been allergic to the use of seasonal factors?though every sabziwallah, and therefore everybody, knows about the importance of seasonality in food prices. Indeed, that might be one important reason why monetary policy in India has not been exactly path-breaking. Given the new modern regime in Mumbai, it is hoped that, sooner rather than later, seasonally-adjusted data will be a standard feature of data dissemination and policy discussion in India.

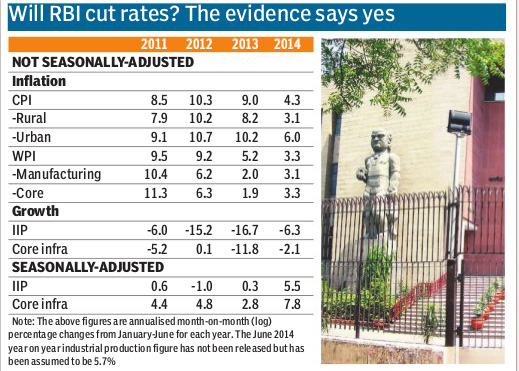

The table reports month-on-month calculations on various inflation indices for the first six months of 2014 and the corresponding months in the preceding three years. For CPI and WPI, only the rates of growth for non-seasonally-adjusted data are reported; this is done to make the analysis transparent and without use of ?strange? seasonal factors (use of seasonally-adjusted data yileds the same results). For the two output variables, IIP and core infrastructure, seasonally-adjusted data are also reported (this is necessary to document that underlying growth in industrial output is beginning to happen).

The inflation trend in CPI, and the old warhorse, WPI, makes for some compelling reading?and provides information about what is happening to inflation. Let us take the trend in the all-important CPI variable first. In the first six months of the three earlier calendar year, CPI averaged 8.5%, 10.3%, and 9.0%, respectively; in the first six months of 2014, CPI has averaged (remember, same basis of calculation of raw, not seasonally-adjusted, data) 4.3%, well less than half the average of the preceding three years.

The trends in the WPI provide for even greater comfort in concluding that the back of double digit or even high 8%-plus inflation is broken. This indicator had averaged above 9% in both 2011 and 2012. Last year witnessed the first significant decline in WPI?down to 5.2%; and 2014 shows an average rate of WPI inflation of only 3.3%!

Over the last few months, the inflation hawks have been twisting and turning to provide some justification to their sheep-like view that RBI should not cut rates, at least until the first half of 2015. I hope Rajan does not hold this view, and the inflation data certainly does not.

As a policy-maker, one has to be concerned with worst-case scenarios. From the inflation point of view, the primary concern right now, and correctly so, is with the possibility of a drought, and its effect on food prices. In FY10, rainfall for the important July-September period was 24% below normal, and growth in agricultural output was close to zero. To date, the 2014 post-June rainfall deficit has dipped below the 2009 mark and rests at 22%. A safe conclusion is that agricultural output may not see much change this year, though chances of positive growth are increasing.

However, what matters for RBI policy is the price of food, and on this score, there are literally mountains of food (rice and wheat) to contain any possible shortfall in production and/or any rise in food prices. Indeed, the price of foodgrains in India has been independent of rainfall for over a decade. Prices do not rise in a drought, and do not fall with surplus production!

Thus, a safe conclusion is that there is no real threat to prices of foodgrains. RBI, and inflation hawks, will have to look elsewhere to make a credible argument. What about oil prices? Senior Indian policy-makers (RBI governors and finance ministers) have been known to invoke the devil of oil prices when convenient. So far this year, Libya, Iraq, Syria, Israel and Palestine (and Russia-Ukraine) have all seen turmoil and by any calculation, this mayhem has been greater than any other post-1973 year. To be sure, there have been wars (Kuwait in 1991) but collectively, 2014 should go down as the worst year for political conflict in the Middle East. And what has happened to the price of oil (Brent crude)? It has hovered around $102-$104 a barrel for the last five years with short-lived spikes in both the upward and downward directions. This is not to say that the price of oil cannot go up sharply; rather, it is to assert that for an economy with very high real interest rates, and well below par economic growth, neither its central bank, nor its inflation hawks, should clutch at straws just to assert that caution has to be exercised until inflation reaches below 5% for three successive years before RBI cuts rates!

Perusal of the historical, and recent, inflation data also helps in understanding the mind-set of the finance ministry in formulating the Budget. Many have criticised financial minister Arun Jaitley for unnecessarily sticking to the 4.1% target for deficit in FY15. If one looks at the growth numbers for core infrastructure and industrial production, a recovery is apparent with IIP averaging a solid 5.5% seasonally-adjusted growth for the first six months of 2014. A GDP growth rate for fiscal year FY15 of 6% is not unlikely. And this will help enormously with tax revenue.

But there might be a larger reason for Jaitley sticking to the 4.1% deficit target. It is to convince RBI that there is an additional reason to cut rates on August 5, and reason beyond the sharp and stable decline in inflation rates.

So, will RBI oblige? The market certainly does not think so. There might not be a repo rate cut (though there should be) but the evidence that some easing of monetary conditions (e.g. SLR, CRR, and combinations thereof) is overwhelmingly in the cards, and stars, but strangely not in the know-all bond and stock markets.

The author is chairman, Oxus Investments, an emerging market advisory firm, and a senior advisor to Zyfin, a leading financial information company. Twitter: @surjitbhalla