The country has a responsibility towards the health of its citizens that translates to creating an enabling environment, advocates Dr Shoibal Mukherjee, independent professional and research consultant

With more than 300 million disability adjusted life-years (DALYs) lost due to disease and premature death, India has, by far, the highest disease burden in the world – China is a distant second with about 200 million. Communicable and non-communicable diseases are equal contributors to the country’s disease burden, each accounting for 40-45 per cent, while injuries make up the rest. The country has a responsibility towards the health of its citizens that translates to creating an enabling environment for investments in healthcare and goal-directed research in health technologies. With its track record of recent successes, the domestic pharma industry, together with foreign investment in this sector, can play a pivotal role in turning the situation around if given the right incentives and a conducive regulatory environment.

The world pharma market is worth approximately $1 trillion. Of this, about $600 billion is sales of patented products and approximately $250 billion is global generics. In the last 20 years the domestic pharma industry has competed successfully in the generics space, capturing about 6 per cent of the market share (excluding domestic sales), amounting to approximately $15 billion in exports. While there is still potential for India’s share of the global generics sales to grow further, a section of the domestic pharma industry now stands poised to enter the much bigger patented products market. The challenge in getting the best value for investments in innovative research, which drives the discovery and development of patented pharmaceuticals, lies in the capital intensive nature of drug development, particularly the clinical research component which consumes 60-70 per cent of the cost and time required to commercialise a new medicine. Indian companies would have a clear advantage over competitors in other countries if they could leverage the significant local cost advantages in research. Commercial successes can help build expertise and capacity in research that could be leveraged to address local disease burden. The training and development of personnel in cutting edge research in a growing pharma sector would be crucial to building an ecosystem for health technology research that would be available for application to the country’s health needs.

However, domestic regulatory hurdles have now made it impossible for the domestic industry to benefit from its locational advantage. Moreover, the country has been unable to sustain foreign investments in this sector, with repeated instances of research facilities being closed down and foreign entities announcing discontinuation of research projects in the country. Far from fostering an environment to support front-line research at a globally competitive scale, these developments have led to an attrition of research capacity and a reversal of growth in research capability. Employment opportunities in the health technology research and development sector have contracted sharply and job losses are plaguing this knowledge intensive high-potential domain.

Lost ground

From 2010 onwards India has witnessed heightened activism and, at times, media sensationalism targeting clinical research. Consequent actions, led by Parliament and the Supreme Court, have put pressure on the government and regulators, resulting in a slew of new regulations around clinical trials. While these regulations have been well-intentioned, their consequences were not well thought-through, and have not augured well for clinical research in the country, with upstream damage to the climate for innovative pharma research and downstream damage to the long-term future of pharma innovation in India.

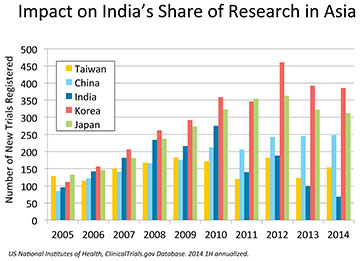

Chief among the flurry of regulations introduced in 2013 has been GSR 53(E) of January 30, 2013, on compensation for clinical trial participants deemed to have been “injured” during the course of their participation. This regulation is not in line with practices anywhere else in the world. Moreover, the quantum of compensation proposed by the government is out of proportion to that paid in the context of other types of injury that trigger compensation payments in the country. The assumption that the cause of an individual adverse event occurring during the course of a clinical trial can be reliably determined prior to completion of the trial is flawed. Typically, such causal relationships can only be determined after a statistically large enough number of patients have been exposed to the medicine through multiple clinical trials or after the medicine has been marketed. Regulatory delays have also taken a toll on research capacity investments in the country. Clinical trial approvals have plummeted from 529 in 2010 to just 73 of 207 applications received in 2013. The length of delays has extended beyond 12 months, jeopardising project timelines. Requirements such as dictation of the type and geographical distribution of sites by the regulatory authority, the elimination of non-institutional ethics committees, and demands for commercial commitments prior to approval of research projects have made India unviable as a global research destination. Consequently, the forward intention of clinical projects and research funding to be directed to India has fallen by 65 per cent from its base in 2010. India’s share of clinical trials among the top 5 countries in Asia has fallen from 20 per cent in 2010 to 8 per cent in 2013 and its ranking in Asia has fallen from third to fifth. Further deterioration in these figures is expected in 2014. Reforms in clinical trial regulation will be meaningless in the absence of significant clinical research activity in the country.

The impact of the research policy has been injurious to all stakeholders. Patients, the most prominent beneficiaries, have lost the option to participate in clinical trials. To many patients with life-threatening diseases running out of conventional options, clinical trials provide a last affordable chance of cure or palliation. Thousands of patients across the country have benefited from participating in clinical trials over the past decade, and some have spoken of their experiences on national television and other fora. Cancer patients have regularly sought clinical trials in the face of resistance to conventional therapy. Others who have lost out to bad policy include research employees and fresh life-science graduates seeking employment as research units close down and fresh hiring comes to a halt. Hospitals that set up research units and employed research staff are unable to sustain their investments, and academic intramural research has become unviable.

The globalising segment of the domestic pharma industry has been disadvantaged the most as the impact on research comes at a time when many companies are on the threshold of initiating major clinical development programmes for novel intellectual property assets. The cost of these programmes is likely to escalate by multiples as trials that could have been undertaken at home now have to be conducted abroad. Economic viability and commercial strategies have to be reconsidered. Significant loss of competitive advantage, at both enterprise and national levels, is inevitable.

Recommendations

The current state and trajectory of growth in health technology research and development is not compatible with India’s aspiration to emerge as a global hub for pharmaceutical research. Nor is it in line with India’s position among the leading economies of the world and its need to address its massive disease burden in a self-sufficient manner in the years to come. It is therefore imperative that appropriate policy changes be made to rectify the situation, and to encourage and incentivise investment in health research and development while ensuring that regulations support the highest level of quality and ethics in research activities. The following recommendations aim to draw a road map to meet this imperative:

Short term requirements

Of immediate concern is the shrinking of established capacity in clinical research and the diversion of research funding by local and international investors to other countries of the region. Early reversal of the prevailing sentiment and regaining the confidence of the investor community will require the following regulatory initiatives to be undertaken with sincere follow-through:

- Time-bound review of all applications: The regulatory agency should set benchmarks for turn-around time of clinical trial applications with an attempt to turn around primary applications in 3 months and secondary applications in 2 weeks. Metrics should be measured and publicly reported for each application. Clear and cogent reasons should be stated in writing to the applicant in case of rejections, which should be based on accepted scientific and ethical principles.

- Rationalisation of compensation regulations: In absence of breach of law/rules, no-fault compensation regulations should apply strictly to study-related injuries (study drug and any study-specific investigation or procedure). The quantum of compensation should be rationalised to approximate the level of payments made by the Government of India in case of accidents and calamities. Medical negligence should be treated as in routine practice.

- Removal of arbitrary restrictions: Hard restrictions, such as on choice of sites, number of trials per investigator, and mandatory video recording of patients, should be relaxed. Sponsors should be free to choose any site that has not been debarred due to misconduct. A system of audits and inspections should ensure compliance to published regulations. Graded action, including possible debarment, should be taken against non-compliant sites. Video recording should be encouraged, but qualified exemptions should be permitted.

If the above initiatives are taken, publicised, and sincerely followed through, it is likely that sponsor interest in making research investments in India can be revived in the short term.

Long-term imperatives

More will have to be done to sustain biopharma research activity in the country over the long term and take the country to a leading position in applied clinical research in the region. Some of the suggestions below have been a part of the vision of previous committees and expert panels. They are reiterated here with some specificity.

- Restructuring of regulatory agency: The regulatory office needs to be restructured particularly in terms of number, qualifications and experience of staff. Induction of a regular head of the agency, preferably with senior-level regulatory experience at one of the world’s leading agencies would be desirable. Other technical officials should be laterally inducted on the basis of experience and technical competence.

- Functioning of regulatory agency: The functioning of the regulatory agency should be based on detailed operating procedures. Databases should be maintained using the latest information technology, particularly for active sites, active trials, and adverse events. A system of online submissions and e-governance should be put in place.

- Technical pre-consultation: A system of formal technical pre-consultation and scientific advice should be put in place for applicants to receive regulatory guidance following best practices at the world’s leading regulatory agencies.

- Enforcement apparatus: A system of regular inspections of clinical research sites, ethics committees, and research organisations should be put in place with thorough training and clear operating procedures for inspectors. Regulations against fraud, data manipulation and misreporting should be instituted.

- Guidance for sites: The regulatory agency should provide guidance to sites that can subsequently form the basis for an accreditation system. At a minimum these should cover standards for operating procedures, documentation systems, facilities for trial participants, patient awareness, trial access and recruitment guidelines.